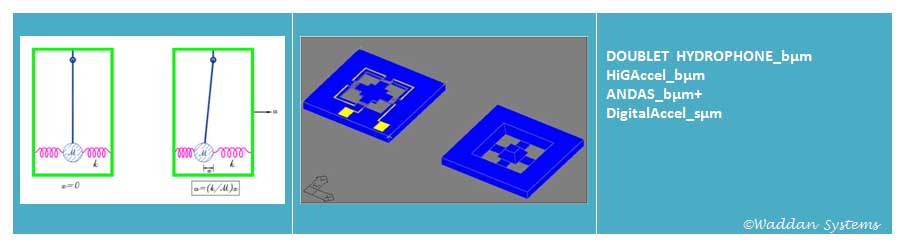

An open loop sensor directly responds to an input stimulus. Its

physical structure is directly affected by the input (e.g. a pressure

change affecting the level of deformation in a diaphragm).

A greater input produces a greater physical change, and thus, greater

output signal. A design compromise is always made between the

measurement sensitivity and measurement range. For higher sensitivity,

one has to

sacrifice the range; and for wider range one has to sacrifice the

sensitivity. In general, open loop sensors operate linearly over a very

narrow range; and have a nonlinear response over the full

operational range. These devices require look-up table calibration, or

some other means of compensation.

An open loop sensor directly responds to an input stimulus. Its

physical structure is directly affected by the input (e.g. a pressure

change affecting the level of deformation in a diaphragm).

A greater input produces a greater physical change, and thus, greater

output signal. A design compromise is always made between the

measurement sensitivity and measurement range. For higher sensitivity,

one has to

sacrifice the range; and for wider range one has to sacrifice the

sensitivity. In general, open loop sensors operate linearly over a very

narrow range; and have a nonlinear response over the full

operational range. These devices require look-up table calibration, or

some other means of compensation.

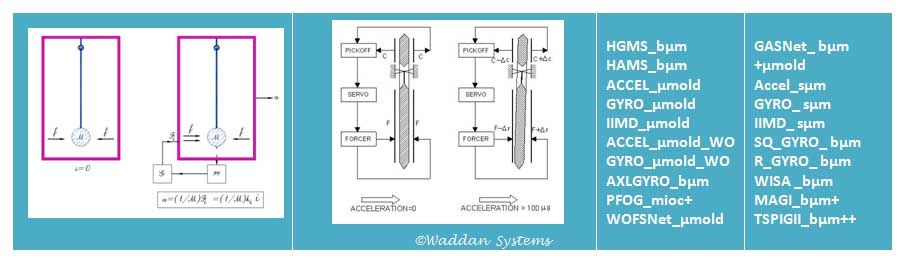

The closed loop sensor response does not depend upon the physical

change of the sensor directly, but upon an indirect measurement. As the

navigational grade accelerometer has to have resolution on the order

of a few micro-Gs, it is designed with an extremely compliant

suspension (a frictionless hinge will be ideal). The micro-G level

change

in acceleration tends to produce a measurable displacement in the proof

mass, which is detected by a pick-off, that in turn generates a

rebalance force to bring the proof mass back to its null (zero G)

position.

The higher input requires a higher rebalance force through a

controller. Thus, the signal that produces the rebalance force to

maintain the proof mass at its null position becomes the measure

of acceleration. Similar differential pick-off, forcing, torquing

or phase nulling approaches are employed in all closed loop sensors.

The closed loop sensor response does not depend upon the physical

change of the sensor directly, but upon an indirect measurement. As the

navigational grade accelerometer has to have resolution on the order

of a few micro-Gs, it is designed with an extremely compliant

suspension (a frictionless hinge will be ideal). The micro-G level

change

in acceleration tends to produce a measurable displacement in the proof

mass, which is detected by a pick-off, that in turn generates a

rebalance force to bring the proof mass back to its null (zero G)

position.

The higher input requires a higher rebalance force through a

controller. Thus, the signal that produces the rebalance force to

maintain the proof mass at its null position becomes the measure

of acceleration. Similar differential pick-off, forcing, torquing

or phase nulling approaches are employed in all closed loop sensors.